the bi-temporal body

talk two

December 2008

Lilian Baylis Studio, Sadler’s Wells London

The Bi-temporal Body

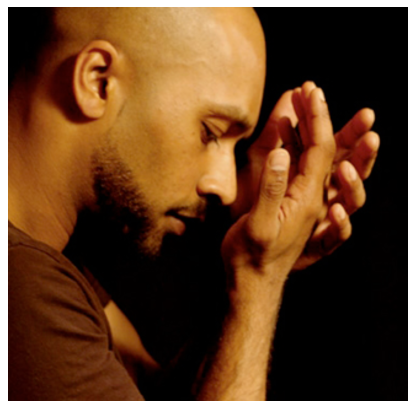

Guy Cools with Akram Khan

Akram Khan

British-born choreographer Akram Khan is celebrated internationally for the vitality he brings to intercultural, interdisciplinary expression. His dance language is rooted in his classical Kathak and modern dance training, which continually evolves to communicate ideas that are intelligent, courageous and new. Khan performs his own solos and collaborative works with other artists, and presents ensemble works through Akram Khan Company.

Previous collaborators include the National Ballet of China, actress Juliette Binoche, ballerina Sylvie Guillem, choreographer/dancer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, singer Kylie Minogue, visual artists Anish Kapoor and Antony Gormley, writer Hanif Kureshi, and composers Steve Reich and Nitin Sawhney.

Khan has been the recipient of numerous awards throughout his career, including the prestigious ISPA (International Society for the Performing Arts) Distinguished Artist Award 2011 in New York, the South Bank Sky Arts Dance Award (2011, Gnosis) in the UK and The Age Critics’ Award for Best New Work (2010, Vertical Road) at the Melbourne Arts Festival. He was awarded an MBE for services to dance in 2005 and received an Honorary Doctorate of Arts from Roehampton and De Montfort Universities.

The memory is in the body.

(Akram Khan, in Letters on the Bridge, a film by Gilles Delmas)

In my theory of the ‘in-between-two-bodies’, the body itself is a complex form,

consisting of a body-being-present and a body-memory, each of which has

another two levels: that of ‘calling out’ (appel) and that of ‘recalling’ (rappel).

Sibony 1995, p.89-90

Guy Cools:

Akram and I first met almost 10 years ago. I was introduced to him by Jonathan Burrows, with whom he had done a choreographer/composer course and who had asked him to perform a duet with him for the 50th anniversary of the composer Kevin Volans at the South Bank Centre.

As a programmer at the Arts Centre Vooruit in Gent, I invited Akram with his kathak work and his first contemporary dance solos. His first full length company piece, Kaash, was partially created in residence in Gent.

Since Zero Degrees, I collaborate with Akram as a dramaturge, and in my reflection on his work I am particularly interested in how intercultural issues are mainly a matter of bridging different times, such as the traditional with the contemporary. Again there is one major book that frames my thinking: ‘Le corps et sa danse’ by the French philosopher Daniel Sibony, who defines dance as a movement between ‘a body-memory’ and a ‘body being present’. Hence the bi-temporal body.

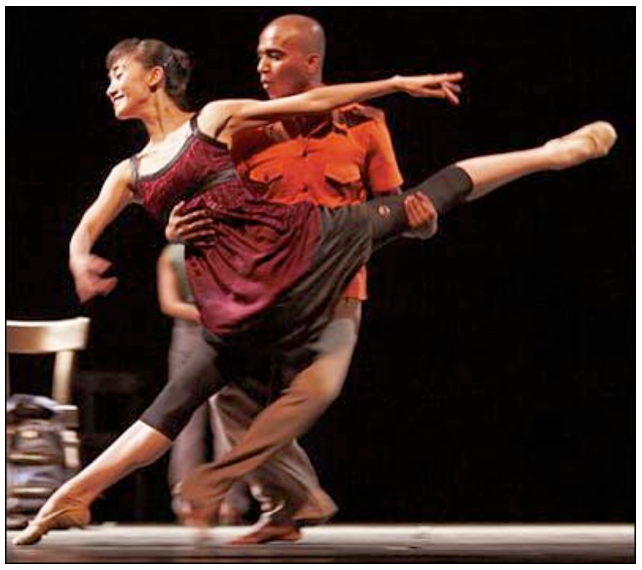

Akram, since our artistic collaboration started with Zero Degrees, I would like to start our talk with what the series of duets that you made with Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Sylvie Guillem and Juliette Binoche added to your knowledge as a choreographer and performer.

Akram Khan

Until Zero Degrees, I had never really explored any partner work. Even though I had done Kaash and Ma, somehow with every piece before Zero Degrees – even if it was a company of 5 or a company of 10 – it would be a solo and 9 dancers. And that was my own problem, or my education maybe, because kathak is a solo art form (as a lot of the Indian classical dance forms are). When I related to people, it was for a choreographic reason; it was not necessarily a physical experience with another body, until I worked with Larbi. In a way that was the most important thing: there was a sharing of energy.

Guy

When I was preparing the talk that I had with Larbi last week, I was re-reading a lot of his interviews, and one of the things I remember he was saying, was how much collaborating with you liberated the movement that was already in him… he was referring to the hand movements that were already very much part of his vocabulary, but that he needed to share with you in order to know how to continue to explore that very personal part of his own vocabulary.

Akram

There are three directions in my artistic work.

As you said – there is the classical work, which is the solo dance form of kathak. Then there is the company work; and then there are the collaborations. I was thinking of it recently, and I think for me the three directions relate to two people in my life, who had very clear influences on one of those three.

The first one is my classical work and that relates very much to my father and my father’s body – because growing up in front of my father’s eyes there was something very classical about him. There was a huge amount of form around him. There were rules, there were regulations. Everything was almost mathematical with my father; he is an accountant, so it does not surprise. But there was a very strict relationship with him, and that comes from his own personal experience. He grew up in a family where he was the head; he had to run his family because his father lost his job and so on. So there was some kind of authority about him. He built all these walls and rules and they were very precise, and so, in the way my father stands… when he turns his head the whole body turns. And his whole way of expressing himself, of course I was picking this up as a child – so in my classical work I relate to him.

And then there is the company work which I would say is much more my mother. With my mother’s body everything is more circular; it is more huggable if you like, and there is something exactly the opposite of my father’s – very formless, very creative. She was a folk dancer; but she adapted, because her father did not allow her to dance. She would secretly go and learn classical dance, and when she wasn’t allowed to do classical dance she would do pop dance, or she would do something else. She was constantly reinventing herself to survive, to stay connected to the arts in Bangladesh at a time when she was not allowed to, and so her body language is much more circular, much softer. That influence – her body influence – comes into my contemporary work.

And the collaborations, I would say, is me.

Guy

Again I am going back to last week’s talk: In the discussion with Larbi I used amongst others a book that you suggested to me, which is ‘The Eye of Shiva’. I think you read it when preparing for Kaash?

The book is a comparison between Eastern and Western religion, philosophy and science. The author says that in Western history binaries like female and male have always been put into opposition with each other, while in Eastern thought they are allowed to co-exist on an equal basis.

Akram

Absolutely.

Guy

It is even demonstrated physically, in the performing arts: in kathak you can go from the male to the female character just in the physicalisation of your body. The second duet with Sylvie Guillem was very different?

It is the dichotomy of the opposites. One place, which is the classical world,

offers you tradition, history. It offers you discipline, something very sacred and spiritual, too.

And the other place, the contemporary, offers you a science laboratory. It offers you your voice

to be heard. It offers you numerous discoveries and possibilities. To be in a position where

you can reach out to both, is the best place to be for me.

(Akram Khan, in the programme text for Sacred Monsters)

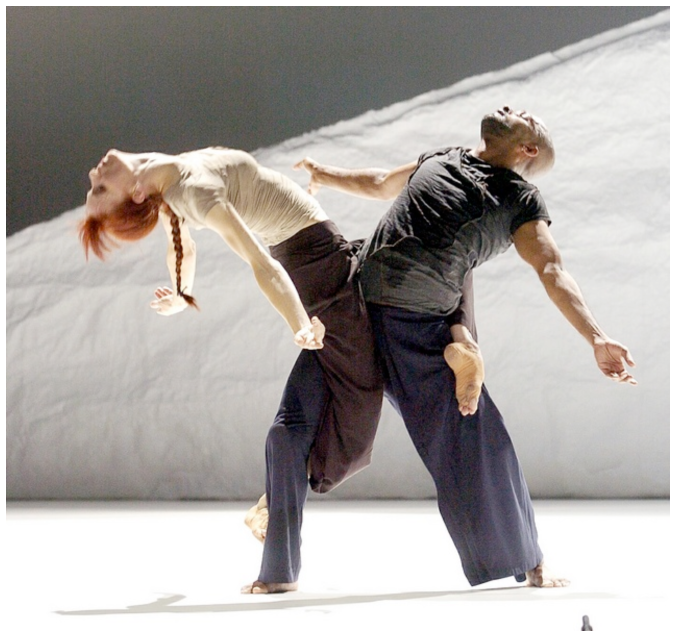

Akram

Both of us were exploring not just each other’s bodies (which was really another completely different experience to working with Larbi’s body), but we were also somehow following a parallel journey. We are both classically trained – myself in Indian classical dance and Sylvie in Western ballet. We were trying to move out of it – but not move away. We wanted to take our experience of the classical with us.

With Larbi it was a male dancer; a male artist – being very in touch with his feminine quality. With Sylvie it was a female dancer being very strongly attached to a masculine quality. She has this kind of real masculine power that is interesting to me. The fact that she was much taller than me created interesting things and possibly new kinds of challenges for me. It was different, because when I was working with Larbi we were embodying each other’s experiences – while with Sylvie and I we did not necessarily share our material. With Larbi it was really a kind of breathe in and breathe out. What I would breathe out he would breathe in, and what he would breathe out I would breathe in… I remember that for three years before we even made the project, I was teaching him kathak.

With Sylvie it wasn’t like that because she does not recognise herself as a choreographer. She is very clear: she is the performer; the artist who executes the work. It was working with a body who is actually very gifted, very sensitive, very creative – but it was really creating material on her body – and also together.

Guy

I remember you worked with Nicoletta as an understudy, and that if you had to change – doing partner work with Nicoletta and afterwards with Sylvie – it was a big shift.

Akram

… because the body is not simple. I wish it was, but it is not. It comes with cultural background, it comes with political background, it comes with historical, religious background…

Each person is unique and so their experiences are unique. We thought of working with Nicoletta because she was one of my dancers and she had been a principal dancer in one of the ballet companies in Slovakia. She has a similar body to Sylvie in some respects, and she has a classical body, but we had to shift everything. The whole rhythm, the whole energy would change because of Sylvie’s background and her own identity, her own way of moving.

Even though the common denominator of these three works is my body in duet with another body, my body is changing because of them. Whether I want it to change or not is irrelevant because being in contact with someone who is so different brings out another side of you.

Guy

And then Juliette Binoche also challenged you, or asked of you ‘the biggest shift!’… to do a tango with her.

Akram

It was the biggest shift – and it was also the biggest gain for me as an artist. Working with a non-dancer, I could not take things for granted the way I did with Sylvie and Larbi. With them, once we were on stage somehow I could trust that they are going to be ok. With Juliette it is not the case, and it is not because of her – it is just the fact that she has no dance experience. She did 4 months of serious training, but it is not the same as doing 20 years of training. On stage I have to be the one who is partnering, but I am also her shadow, so I play my own shadow in order to protect her.

For this particular project, I abandoned my own body and started with her body. I felt that if I had generated material for my own body for her to learn in 4 months, it would not have been possible, so I had to start with a blank canvas, which was her body. To abandon your own body, which you trust so much, means that you are teaching your body something new already.

Guy

I would like to go back to Zero Degrees. You prepared it over a very long period – about a full three years. Before you actually started rehearsing you had regular meetings with Larbi, talking about the ideas but also going to the studio and trying out some ideas. I was very privileged to witness this. I remember coming into the studio in Gent – and you were trying out kathak rhythms on all fours at that particular time (which I am very happy you did not develop), so originally I think there was an idea to develop a new language – out of this coming together of two people…

In the end every section of the piece has a very clear identity, that was either initiated by yourself or by Larbi. The video clip which I would like to show is from the end of your story, which is a story of you going back to India. There is a whole story about identity and borders, but then at the end it becomes about death, because you discover a dead person on that journey.

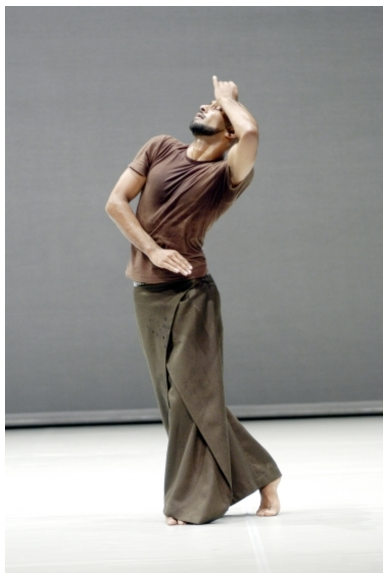

First you tell the story in Larbi’s hand movements, and then you retell the story in your language, which is a form of abinaye. Could you comment on how the abinaye was developed in this particular piece – how much of it is traditional and how much of it is new?

Video clip – Akram’s classical solo from Zero Degrees

Akram

What is interesting for me, seeing it back again, is the sense of questioning. It brought back the memory of why I am attracted to work with artists who are from different backgrounds. Larbi was a huge fan of gymnastics (he had studied some form of gymnastics), but he also came from the pop world.

I was asking myself why we decided to work together, and I think it is because we want change in our own body. Working with Larbi, with Sylvie, with Juliette, it was very much about that – it was about not just what work we can create, but how our bodies will change.

You see yourself in the other person – and I think that is what happened with Larbi, and vice-versa. But the other thing you notice which is very important, is the face that you notice something that they have that you don’t have. When I see this section it is very much like that. The root of it is the traditional language of kathak, but it has been transformed completely through improvisation, because of me working with Larbi. It is a contemporary piece of work, not purely a classical piece of work.

Kathak has very particular dimensions, for instance the boundaries of how far the gestures should go. Of course it depends on the guru and what style it is, but underneath it, like Maharajee said (Maharajee being my teacher’s teacher, who is a torch bearer of kathak) when he saw something of my work, funnily enough on youtube apparently… they said, ‘this is a contemporary piece work’, and he said, ‘No, that is kathak – that is a kathak body for sure’. He could identify.

By working with Larbi, and by my own experience of venturing into contemporary vocabulary, the abinaya is not in the framework of a kathak repertoire, and so, in a way, it is very distorted.

Guy

From an early stage in your career, you have been publicly and very consciously rejecting the notion that your work is about fusion.

Akram

Yes.

Guy

But you have been talking about confusion – on the level of the body.

Akram

‘Fusion’ feels too much like perfection. It is a perfect thing, where two things fuse together to create something that becomes one. It is too much of a fantasy for me. I find it much more complex. The world fusion feels trivial. I had been studying kathak for some years, and then, when I went to university to get away from my community and my parents, my mother said I had to get a degree. So the contemporary dance started to infiltrate into my body and my body started bringing up questions. Not consciously, but through the body. My teachers would notice it… My kathak guru would say, ‘that is not kathak anymore. You are re-routing energy through a different way’, and the same thing would happen with my Graham teacher or my Release teacher. The sense of chaos in the body, or the confusion, seemed a word that was much more relevant to the state I was in then, and the state I am in, even more now…

To remain in that seems important for me. I have a sense of real clarity in my kathak. When I am doing kathak I am at home. It is about wearing the costume, eating… you know, I have to eat bann, because I have to feel like I am in India again. There is a whole ritual, because I feel so separated from it for most of the year.

Guy

Fusion seems to be about blending and eliminating the differences. It is different from confusion. I mean, ‘con’ is also ‘two’, no? So it is like ‘fusion’ to a higher degree, where you keep the differences.

Akram

Absolutely.

I met them first in a land where borders

Get blurred; where day rises before night’s end

And water morphs into high, brumal walls.

A warrior and a monk, two beings –

Flanked by shadows that grow and roam at will –

Cross-legged in thought, carving with four hands

Arabesques on force, loss, fear

[…]

(Karthika Nair 2008, Zero Degrees: Between Boundaries

From the Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Indian Poets, p.315)

Guy

To finish with Zero Degrees, I brought up a quote from the beginning of a poem that was written about the piece by the Indian poet Karthika Nair, which has just been published in an anthology of contemporary Indian poets. It is a beautiful poem in a very classical form, especially in the way that she describes the relationship between the two of you. She calls you a warrior and him a monk. Are you happy with that?

Akram

To a certain extent I am – but I think there are both in both of us. I think that a warrior is only a warrior when he has the monk in him and vice-versa. But for the piece I think it is a really nice way to describe the two characters.

Guy

I would like to go now to the group work. I have only been involved in the creative process of bahok, but I have seen the other ones several times, even during the rehearsal process, and it seems to me that there has also been a big shift there. Whereas in the earlier pieces – like Kaash for instance – it felt like a lot of the material was still developed on your own body and passed on to the dancers, in bahok you really use as the building stones of the piece the dancers’ own movement vocabulary. Is that true?

Akram

Absolutely. In bahok I was putting my body aside and using only part of my body which is the kathak eye. Whereas with Kaash it was very much about using the kathak material of my own body. In bahok I was exploring their body and each one was very different from me. It was like a circus of different experiences.

Guy

What you say now reminds me also of an interview that you gave during the period of Zero Degrees. There was a special issue, I think it was in The Independent, on the body and they interviewed yourself and Antony Gormley. You said something about the different experience of seeing it from the inside, and that you need to see it on other bodies too, to develop an understanding of it.

Akram

The other day I was talking to the Artistic Director of the National Portrait Gallery about the portrait that Darvish Fakhr did of me, which is a series of portraits of me in nine different emotions. We were talking about the painting and how the painting does not change, whereas live performance does change every time. He said, ‘no – that is not true’, and I now agree with him. He said a painting does change, because when you first see a painting you have taken it in. But then you go away and when you come back you see it in a different way. You transform it, because you have gained a different experience. It is like the Indian time-cycle, which is in a circle, in a spiral effect.

Guy

I just had a similar experience this week when I went to see the Rothko exhibition. You do not even have to go away while you are there, it changes because of how your eye adapts to the space, to the light changes. The painting starts to be alive.

In bahok you worked with a group of dancers with very, very different backgrounds. There was the collaboration with the National Ballet of China, and you decided to bring this group together by exploring more theatrical devices.

Akram

It was tough because we did not know how they would deal with the theatrical aspect. The ballet dancers hadn’t ever done anything like it, even though they know narrative through their characters. But playing yourself is a different kind of theatre.

On the first day, I remember arriving late, and the National Ballet of China dancers were in one corner and I think Kim Young, the Korean dancer, Shanell, Lali and Sadju were in another corner, and Chia-Ying, who is Taiwanese, was still another corner. I came in late on purpose, because I wanted to see what would happen without my injection, without them having a reason to come together, and I was hoping that they would all be speaking to each other – but nobody was talking to anybody…

The Chinese dancers were in the corner talking to themselves, my dancers were talking to themselves, and so in a way, they had created walls – because of culture, because of religion and because of the body, because the body has had a different education, physical education. It was difficult when we had to decide what class would we give every morning, because the contemporary dancers were not sure whether they wanted us to do ballet; and the ballet dancers were not sure whether they wanted to do contemporary. Once I came in I immediately decided that we were going to start not from moving, but from the most primal thing – which is to tell a story. I asked them to tell me a bit about themselves. We chose as themes home, a dream, a nightmare…

Guy

Is is necessary for work to be autobiographical?

Akram

No, it is not necessary at all. I think it is maybe necessary for me at this moment – but I am thinking that the next few projects that I want to do should not be autobiographical. If I work with something that is not autobiographical, you still have to find something of yourself within the character that you are playing, or the piece.

Guy

I do think that a work of art needs to have an autobiographical element. The fact that you start from their story and not your story means that they own it.

Akram

If I do Oedipus or Hamlet, or something like that, it would not be an autobiographical thing, but I absolutely agree that you have to find something that is in your own life that relates to that story in order for it to remain, for it to feel real, or to be, as you said, emotionally charged.

Guy

Your work is being presented on all the world stages. In the reception of it, does it also change? It was a topic that came up last week, with Larbi. How much he is still surprised by how different the same piece is received in a different country by a different audience.

Akram

It is a whole subject in itself to understand why the audience react in the way they do – I remember when we did the Mahabharata with Peter Brook – even as a child I noticed the differences. I remember there was a very dramatic, a very, very difficult scene with one of the main characters. His wheel chariot got stuck in the mud and it was a very important moment because he was about to die. When we were playing in Japan, suddenly, the Japanese audience started to laugh at such a tragic moment. It was fantastic, we were just completely shocked. For me it was really a culture shock.

Does the work change? Yes – the work changes – but I feel more and more it is not because of the reaction of the audience. In the beginning I thought it was, but it may be more because of feedback from people that we trust as artists. Something someone might back picked up on, and so we include that, evolve, and put it into the work somehow.

In the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris – one of the most prestigious theatre houses in the world – the audiences are unpredictable. They are a hardcore, classical Indian audience, funnily enough, and a hardcore contemporary audience. It is the most difficult audience in the world. We were doing in-i and maybe 5-10 people were screaming and saying, ‘this is crap, this is rubbish’, and then the rest of the audience went crazy and started being positive and so you had this whole dialogue between them, and we were not involved. Suddenly they are having a fight amongst themselves. The more some booed – the more others would start cheering.

Guy

Maybe it is cultural… I can imagine that the French want a subject to talk about, any kind of subject. You are offering them performances for them to talk about and disagree with.

Akram

It is interesting. Talking with Nick Hytner, the Artistic Director of the National Theatre, he said that the British audience at the National are more content based, while the French audience… I am generalising, but the French audience are more emotional.

This slippage between the lived body and its cultural representation,

between what I call a somatic identity (the experience of one’s physicality)

and a cultural one (how one’s body – skin, gender, ability, age, etc… –

renders meaning in society) is the basis for what I consider some of the

most interesting explorations of cultural identity in dance.

(Cooper Albright 2001, p.47)

Guy

Going back to bahok: Bringing all these diversities into the piece – how did the audiences in different places react to it? The dancers and performers came from all these different places and you kept some of their vocabulary and their own very clearly recognisable cultural identity…

Akram

This is difficult to say, because I haven’t been on tour with them. In India and China particularly, there is this very interesting revolution of contemporary dance going on at the moment, and it is still being discovered. There is a strong sense of their cultural identity in the work, but I always feel that we have to be careful with the ‘Green Card’, you know, ‘this is a cultural thing, we will get attention for that’. It has to be deeper than that.

It can’t just be the effect of bringing together different bodies – there has to be an internal reason for me of why. This subject of these different people coming together in a station was because of my own experience of working, of being in Japan, where I was in a lift – did I tell you this story?

I was in a lift… and… well, that is where the idea came from, an elevator. There was this huge world conference happening, and I got on the lift, and as I was going up, just before the doors closed, a Japanese woman came in who was wearing this very traditional Japanese outfit, and an African gentleman came with a very traditional African outfit. There was an American guy with a suit and two Europeans, but it was difficult to say where they were from. So we were in this tiny lift, and there was an awkward silence, and everybody was trying to find a space to look at. We were all either looking at the ceiling or doors. The kimono dress was phenomenal, and I wanted to ask so many questions, but there was this fear… We were in close proximity and I didn’t know what she would think if I asked her, and anyway there would be a language problem – lots of walls being created in such a tiny space.

In the silence we were going up in this lift – and the lift gets stuck. The first minute nobody says anything, everybody is very calm. Zen. When we realised that nothing was going to happen, everybody started talking, at the same time, and it was interesting that in a moment of crisis everybody comes together regardless of language, culture, or how you look. I am trying to explain to the Japanese woman that there is an alarm – ‘we can ring the alarm’ – and at the same time ‘… but can I also ask you about the colour of your kimono?’

It was so fascinating that at the moment of crisis suddenly we felt that we were the only people in that lift. That experience was always in me, and I felt that somehow it came back in the company work when we were stuck. And out of being stuck in that certain place, we all realised that we had something in common: we all wanted to go home. There was a reason why I wanted to work with these different nationalities – it was not just the fact that there were different nationalities, but there was also a personal story that I experienced.

Guy

I propose we look at a fragment of the final result, and I have chosen the first really big group section of bahok. What is amazing for me is that the piece does introduce all the individuals and their stories, their movement language, and the way that they are connected. And then you have added into it some of your own signature – which is a sense of rhythm and a sense of speed that comes from the kathak – so I think it is very, very rich.

Video clip of bahok – first big group section

Do you think you will re-work some of it when the dancers from the National Ballet of China leave?

Akram

For sure – the essence of it will be there, but with three new dancers… even one dancer will change the whole work. The new dancers will not contribute necessarily as much as the original dancers because those dancers’ bodies and minds all contributed completely to the work. They will have to find a compromise.

Sometimes that is a very interesting process: to find yourself imprisoned, if you like, in a structure, and then to find your own freedom within that. That is what I have always tried to find in my own work. For me kathak became a prison, and at a certain stage in my life I felt, well, how do I continue to find the freedom in it? How do I find Akram within that? Because it is so much about the guru’s knowledge, and there is a very strong sense of right and wrong.

I think that is what will happen with bahok: the new dancers will have to find their space.

Guy

I would like to thank Akram for being here with me. And I would like to thank you for being an attentive audience. Thank you for being with us.

Akram

Thank you, thank you.

Books:

Sibony, Daniel; 1995, Le corps et sa danse, Editions du Seuil, Paris

de Riencourt, Amaury; 1980, The Eye of Shiva – Eastern Mysticism and Science, Morrow, New York

Nair, Karthika; in Thayil, Jeet (ed.); 2008, The Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Indian Poets, Bloodaxe, Tarset

Cooper Albright, Ann; 2001, Moving Contexts, in: Pontbriand, Chantal (ed.), Dance: Distinct language and cross-cultural influences, Parachute, Montreal

Works mentioned in this talk:

Kaash

Zero Degrees

Sacred Monsters

In-i

bahok

Notes:

Nicoletta –

Abinaye – Abhinaya is a concept in Indian dance and drama derived from Bharata's Natya Shastra. Although now, the word has come to mean 'the art of expression', etymologically it derives from Sanskrit abhi– 'towards' + nii– 'leading/guide', so literally it means a 'leading towards' (leading the audience towards a sentiment, a rasa)

Comments Off on the bi-temporal body