the musical body

talk four

December 2008

Lilian Baylis Studio, Sadler’s Wells London

The Musical Body

Guy Cools with Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion

Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion

Born in 1960, Jonathan Burrows danced with the Royal Ballet for 13 years before forming his own company in 1992. Since 2001 he has concentrated on one to one collaborations with other artists, including six duets to date with the composer Matteo Fargion. Both Sitting Duet won a 2004 New York Dance and Performance ‘Bessie’ Award, and Cheap Lecture was chosen for the 2009 Het Theaterfestival in Belgium. Other high profile commissions included Sylvie Guillem, and William Forsythe’s Ballet Frankfurt.

In 2002 he received an award from the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts In New York, in recognition for his ongoing contributions to contemporary dance. He is a Guest Professor at Hamburg University, Berlin Free University and Royal Holloway, University of London. His ‘A Choreographer’s Handbook’ was published by Routledge in 2010.

Matteo Fargion was born in Milan in 1961. He studied composition with Kevin Volans and Howard Skempton. His interest in contemporary dance began after seeing the Merce Cunningham Dance Company perform at Sadler’s Wells. This experience encouraged him to apply for the International Course for Choreographers and Composers in 1989, where he first wrote music for dance, and through which he met the choreographer Jonathan Burrows with whom he has collaborated since. Burrows and Fargion have made a series of six duets conceived, choreographed, composed, administrated and performed together.

Matteo has worked with other choreographers including Lynda Gaudreau, Jeremy James and Russell Maliphant. Over the past 15 years he has developed a strong collaboration with Siobhan Davies, writing music for

and performing in some of her most significant recent work. He also writes for theatre, particularly in Germany, where he has worked at the Residenz Theater Munich, and at the Berlin Schaubühne under the direction of Thomas Ostermeier. He is also active as a teacher, giving workshops and lectures internationally, and is a visiting lecturer at PARTS in Brussels.

Rhythm can restore our sense of embodiment.

(Oliver Sacks in ‘Musicophilia, 2008, p.382)

Guy Cools

Thank you for joining us, and in Jonathan’s case, coming especially from Brussels, where he is now based.

This is the last of four talks, and I am very pleased that it is with both of you, because you were my introduction to British dance when I started as a very young presenter in the early 90s. Being very generous artists, you also introduced me to Rosemary Butcher and to Akram Khan, who I have both now interviewed as part of this series, so it feels like things have come full circle.

In any other art form, people tend to look at a body of work as a whole journey, whereas in the performing arts – because of the temporality of it – we always look at the most recent piece. I appreciate that in these talks the conversation is not connected to one particular piece, but that we are going through the whole body of work. I have been enjoying preparing for each talk, looking at all the old work and re-reading things that had been written about it, and that I had written myself.

The two of you have worked together for almost 20 years now; a relationship that has changed and become more and more intimate. You also recently revisited The Stop Quartet, which is like an iconic piece half way through that journey. You were mentioning earlier that when you look back at some of your older work, it does still feel like there are elements that are still very valuable for you.

Jonathan Burrows

The temporality of dance is of course a fantastic quality, and very liberating because it means that to a large degree, as dance artists, we are not surrounded by the constant presence of the history of the art form. There are many ways to record it, on film or video or computer, but they are a representation of the performance, they are not the performance itself. So it seems to me that this is something that has allowed dance to go on reinventing itself with each new generation, so that ideas recycle but by the time they have recycled they seem to have already shifted. I think that is why dance remains one of the most experimental of art forms.

On the other hand, I think every artist inevitably has a longing, that at a certain point they might look and say, ‘well, here are four or five volumes of poetry which exist, as tangible objects’. But poets rewrite also. Wordsworth was notorious for constantly trying to revise his earlier work, so that with The Prelude, which is the poem about his childhood in the Lake District and his travels to France – when you buy a copy of the Penguin edition, there are two parallel versions, because the final version was so different to the first. Choreographers don’t have that problem – we can revise our performance every night if we want to.

Matteo Fargion

People say it is different every time anyway, even if we do not change anything.

Jonathan

We performed Both Sitting Duet last Friday in Berlin, and there was a lady who has written about it, so she had really watched it a lot. ‘Oh’, she said, ‘I have analysed this performance, and you didn’t do the same piece tonight.’

Matteo

She seemed quite cross!

Jonathan

And actually we had done exactly the same piece.

Guy

Somehow it is related to why I brought in Oliver Sacks. There seems to be a very strong element of memory: our memory immediately changes reality. At my university there was a brilliant teacher who wanted to research the memory of audiences after performances. They set up an experiment where they made a show specifically for the test, and they were going to interview audiences. His original idea was to interview them immediately afterwards, again six months later, and then again a year later, to find out if the memory gets less and less clear. That was his hypothesis. But the first questions, immediately after the performance, showed that people already remembered things completely differently than what they had just seen, and when they were confronted with the video material of the actual performance, they said the video had been manipulated. They trusted their memory more.

For me, what has been so fascinating about you, is that there seem to be underlying themes that you have been researching very rigidly, over and over and over again, in different forms.

Jonathan

I was going to say one more thing about audience memory: there is a fantastic book called Rites of Spring, which is a discussion of the ideas of Le Sacre du Printemps and what the piece meant, but also what the very strong reactions to the piece were when it was first shown; what it meant in parallel with the awful violence of the First World War. The author tracked down all the people who claimed to have been at the first performance, where there was this famous reaction from the audience, and he showed that it was actually impossible for a number of them to have been there. There was strong evidence that some of these people were in fact somewhere else that night, and that what they had seen was a later performance, but they had genuinely come to believe that they had been at the iconic first performance.

But yes, there is no doubt that the perception of an audience changes. It is a thing that is as much alive as the piece itself in performance.

Guy

Do you have a memory of the original desire to collaborate, the original kind of subjects that you wanted to explore together?

Matteo

My memory is that we met through a mutual friend, who was a composer. He took me along to see Hyms, and apart from finding it very funny, I could see already an interest in structure, musical structure, which I liked. In fact I think I said to Jonathan straight away that I liked it because I found it very abstract, which I was surprised at, because it was very personal material; but somehow the way it was presented seemed to be very abstract.

So that was that, and I remember then playing some music to Jonathan when he came for dinner, after having charmed him with food. It was a short piece that I had written called Five Frugal Pieces, which was very reduced and for me quite similar to Hymns in the way that the structure and very personal material co-existed.

Jonathan

Do you remember the piece?

Matteo

I remember that you really liked it and then commissioned me to write the first piece we did.

Jonathan

What I know is that during the Mozart Bicentennial I came out of the closet and realised that I didn’t like Mozart yet (and my fear is that when I am 75 or 80 I am suddenly going to get it and there is not going to be enough time to listen to it all). But the person that I do love is Haydn, and in Matteo’s household I have never been allowed to listen to him. And then, finally, because I bullied him into listening to Haydn’s The Seasons, Matteo said, ‘But you just like very flat music’ – because I like Haydn, reggae music, English folk music, hymn tunes and so forth – but the awful truth is, it is partly what attracts me to the music that Matteo writes.

Matteo

No comment.

Guy

You just re-lived The Stop Quartet. Was this also an exercise in revisiting, like you mentioned that Wordsworth revised?

Jonathan

There were a few reasons why I wanted to re-do it. I had always thought that I should do it again while there was a chance that physically I could still manage it. And even then I wasn’t going to be in it, but Henry Montes bullied me into doing it because he said, ‘I won’t do it unless you do it’, and I said, ‘I’m too old and very stiff, and it will hurt’. But I trusted him and actually it did not hurt, and it was a fantastic piece of research for me to re-investigate a previously occupied body, as it were. But the reason I wanted to do it again was because from time to time there have been a number of people who have lamented the fact that while The Stop Quartet is a dance piece, what Matteo and I do has moved in a different direction – and I wanted to show, to myself and to them, that actually The Stop Quartet is the same work.

It was very interesting for me performing it, because when I walked on stage, and when I came off stage at the end, I felt exactly like Matteo and I had been performing any of the three duets that we have made. The inner life of it felt the same, the rhythmic relationship between performers felt the same, and the play in it felt the same.

I am not sure that you can always control the trajectory of the work that you go forwards with. I found a fantastic quote by Francis Crick the other day, who, along with James Watson, discovered the double helix form of DNA, for which they won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1962. Francis Crick said, ‘It is true that by blundering about we stumbled on gold, but the fact remains that we were looking for gold’.

I thought this is such a joyous description of the actual process of an artist working, because it is very easy to reframe your work with greater clarity after the event. I am an obsessive reader of interviews with artists, and I always come away thinking, ‘But they knew what they were doing and I don’t know what I am doing.’ But I suspect that actually none of us knows what we are doing, and we do just blunder about, and the only thing is to have image of the gold that you are looking for; somewhere out there.

Guy

How was The Stop Quartet for you, Matteo? You worked with Kevin Volans to compose the music.

Matteo

How was it to re-see it? I recognised a lot of the material and that was quite interesting. I mean, from the pieces we have made since…

… or if not the material, then maybe the tricks of the trade. I was able to see the choreography in a very different way now. When I was watching it as a composer, I had no idea how it was made and I could not imagine the complexity of it. Now I just thought, yeah, I know that, I know how to do all that. It did not seem like a museum piece. But I agree with Jonathan that the relationship between it and, say, Both Sitting Duet is very close, or with The Quiet Dance.

Jonathan

I have been trying to write a book for choreographers, reflecting the multiplicity of means which we are now using. I had been leading a series of discussion workshops and I had written down a huge amount of material from many, many different artists, to use as a resource. And I asked Matteo one day, ‘Could you give me a quote for the book?’ It was quite amazing, he did not even hesitate to blink his eyes, and said, ‘Stealing from yourself is good, but stealing from others is even better.’

But now he is upset because I did not put it in the book – it was too good. It was very clear when we saw and when I danced The Stop Quartet that the amount of stealing from ourselves was huge. There is a movement which comes from Hymns, which I made in 1988, [shows the movement] and I have used it in every single piece I have ever made. Not in the kind of ‘this is my signature’ way; it is just out of pure laziness, because the movement does something that at a certain point I always want a movement to do, and then I think, ‘well, what is the point of making a new one, I have that old one’. And the truth is that not one single person has ever noticed that I do it in every piece.

Matteo

Except me.

Guy

Do you remember when we had this public talk in 2000 at the Royal Opera House, which was part of the Catalytic Conversations with Antony Gormley?

Jonathan

Yes.

Guy

And you came to that talk with a very long list of questions, which were all very pertinent, and I feel like you have answered a lot of them, but still you are asking the same questions. So I would like to put the whole list up on the screen.

– What age am I when I perform? Can I dance the age that I am?

– Where does the image of my dancing-self come from? What part is mine and what part is still trying to please the people who taught me?

– Is it sometimes humiliating to dance?

– Can I use the useful information my body has absorbed and separate myself from what is no longer appropriate?

– Can I use the language of ballet and separate ignore that it represents also the body as a site for the representation of wealth and privilege, of the colonial? What other bodies posses me from the past?

– Since the search for perfection has been so much a part of my training can I ever let it go?

– How do I translate the physicality of another person onto and into my own body? How and when might I repossess my own body, my own dance?

– How would I move if I dared?

– How do I move when I don't question how I'm moving?

– Do I have to be a virtuoso? Do I want to be a virtuoso?

– Why do I want to perform?

– How is performance different from life? How is it similar?

– What is extremity in performance?

– How is technology changing my relationship to my body?

– Is this a personal journey?

– If this is shared then what am I inviting people to share?

– What can the audience take from or give to a performance?

– What is the performing space?

– How do I bring the performing space into focus?

– Is it more eloquent not to speak?

– What does 'too meaningful' mean?

– What is repetition?

– How shall I keep notes?

– Am I asking questions that have already been asked?

– Can I accept the contradictions?

– How can I simplify all of this?

Guy

For me it was amazing that you articulated all of this in such a particular way in 2000, because it seems to me that it was a kind of programme for the duets that the two of you have made together, right?

Jonathan

Yes. I found in a notebook from about that same period that I had done an exercise that was called ‘Ask yourself 10 questions a day for 10 days and don’t answer them’. So I thought I would try it again.

Guy

And you have probably come up with the same questions?

Jonathan

Well, it was a mixture: some questions circled back and some questions appeared to have moved on. But there certainly is a carrying forward of thoughts, although for that talk in 2000 I was trying to do something slightly less personal, that I thought might be more universal.

Matteo

How do you mean, Weak Dance?

Jonathan

Weak Dance Strong Questions was a piece that I made with the theatre director Jan Ritsema, where we moved for 50 minutes in silence: two bald, middle-aged men moving as though we would ask a question. And we thought that we would do it just a few times for our colleagues, but then it kind of became a success and we performed it a lot – and eventually I stopped it because I felt that I would go mad if I asked any more questions, and that I wanted to go back to making the kind of work which makes statements, which is what Both Sitting Duet became.

But I think also that this list of questions reflected something across the field of dance, which is about the crises as to whether movement can be valid as a subject matter in itself.

Guy

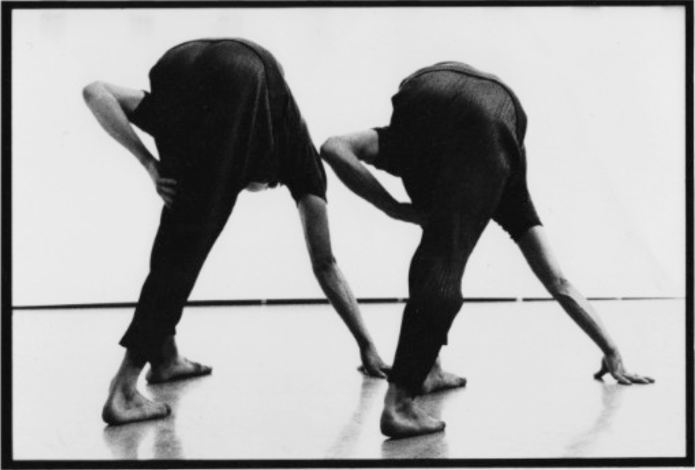

Matteo, let’s step into the performance aspect of it. You have always been performing as a musician. How was the step into the movement part of it?

Matteo

It came about by seeing Weak Dance Strong Questions and thinking that I was missing being on stage and performing. It is as simple as that. We talked again about how we could work together, and I suggested that maybe I could be on stage again. I am a musician, but I have never really had an instrument that I could perform with. From being a teenager I had played the bass guitar, but nothing that would give me the satisfaction that I get from these pieces, so it was a purely selfish request to start with. And then there was the desire to find a way that we would be more equal, if you like. ‘Let’s do a piece in which you don’t just write music and I move – let’s both make this piece, let’s both perform’.

At first the only way I could think of it was treating it like music, tricking myself into thinking I was playing a percussion piece, which is a trick I sometimes still use. Depending on the performance, the accuracy of the movements comes very much from the musicality: the score is written musically and I am just performing that. The fact that it is bigger movement and does not actually produce sound is immaterial.

Jonathan

I think there has been a much greater acceptance and interest in untrained people dancing and performing. It has partly to do with this question about movement. For myself I had reached a point where I had become obsessed by virtuosity in the body – and I am not even particularly virtuosic which made it worse – and I felt like I was searching to find more and more complex detail in the body, and yet I could never make it as articulate as William Forsythe. Basically.

I felt like I had reached a dead end, both personally in my own body, but also working with dancers. By working with people who were not trained dancers, I suddenly saw movement again freshly. It has to do with the efficiency of the body, the way the body makes a movement more and more smooth, which starts at a certain point to render it invisible. The analogy I always give if I am talking to people in workshops, is that if you are cleaning your teeth with your right hand, you are hardly aware of what you are doing (If you are right-handed) – but if you clean your teeth with your left hand, it suddenly becomes an evident activity.

And when Matteo first started performing movement, that was what I felt. It was like a re-training in movement for me, but not from the direction of technique. Matteo’s body was spontaneously negotiating patterns which were actually very difficult for him, and by me watching him negotiate those patterns, my own body was reminding itself of its own negotiation at a certain point, and therefore being refreshed. Having said that, Matteo has been on the road now for six years, and he has done 170 performances, so he cannot really be called an untrained dancer anymore.

Guy

How much of it was consciously inspired by Hands? There is a huge resemblance.

Jonathan

You mean with Both Sitting Duet? Yes, we always wanted to do something with Hands and we tried to make a video installation with multiple screens. The original film of Hands was very short (to fit the format of the Dance for Camera series for which it was made). It was 4 minutes 37 seconds.

We did not know much about the medium of installation, and so it was quite poor, but the idea remained somehow unfinished business. We have tried to liberate ourselves from the thought that we always have to make something new, because I am not really a very imaginative or creative person. I just like working: I have my moments, but it is not like I live in a wonderful dream of ideas; I have hardly any ideas.

We like the thought that we don’t have to reinvent ourselves, but rather to re-invest, so to us it is about, ‘What did we not do that we wanted to do, and why did we not do it?’ Usually it is because we think somebody else has already done the idea, but if it keeps coming back, like with the walking in The Quiet Dance, we just say, ‘Well, let’s do it anyway’.

So Hands was part of a pattern of re-investing in things that we had tried and abandoned. We abandon a lot, we throw away a lot. We have thrown away whole pieces. We even at one point threw away three whole pieces in a row, which is partly why we live in a strange kind of funding void, because we are unable to frame what we do in a way that makes sense in a funding context. We never know what we are doing. We don’t start something new until we finish the thing before, and even then we cannot do that straight away, because we are still processing what we have just done.

Guy

I have a strong memory of a dinner at your apartment, where Matteo said, ‘We have made a piece, but we decided to throw it away and start something new tomorrow.’

Shall we have a look at Hands?

Video of Hands (whole piece)

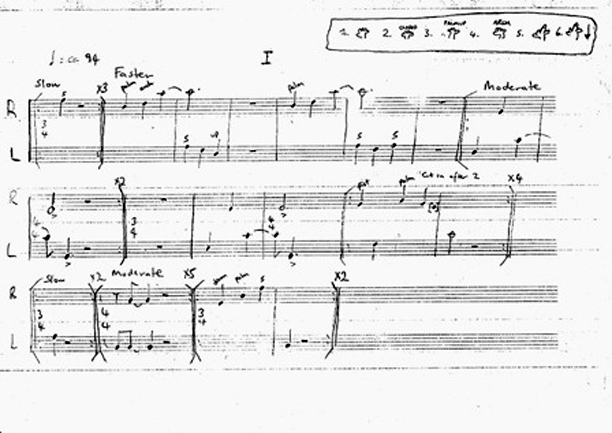

Jonathan

The first minute and a half was choreographed by Matteo, not by me. I had given him six gestures and asked him, ‘Can you write these as music, so that a musician could sight-read it as gestures?’ I thought that they would be very rapid, like a piece of Bach keyboard music, but he turned up a week later and then did this kind of incredibly plodding slow…

Matteo

Flat music!

Jonathan

Flat music, yes, and it never changed. I still have the original score of Hands that Matteo wrote. In a way that process of translating, of squeezing movement into musical structures, was already there then.

Guy

Guy

Because Hands was made for film, it took a long time before you decided to also do a live performance of it.

Matteo

I forgot about that.

Guy

I remember when we were preparing for it, that somehow it didn’t work as you wanted it to, as a live version, until you came up with a solution, which was to amplify very, very gently the hand movements.

Matteo

Did we do that?

Jonathan

Yes, I remember.

Guy

And I also have memories of discussions about how the visual and the auditory function together in that way, and it seems to me that a lot of your work has been an exploration of this.

Jonathan

We have become very aware that visual rhythm is much weaker than auditory rhythm. That is why physical performance can either be really held up and shifted by sound, or it can be crushed by sound. So, for instance, if we amplify the sound of the hands, it is just so that you notice the rhythm of them, because otherwise, even if what Matteo was doing was very delicate on the piano, the rhythm of the movement would easily become something muddy. A little bit of amplification really helps to equal the weight of the two parts.

Guy

The other thing that you mentioned was the idea of researching scores, and that is really what you have been doing with the three recent works. Can you comment a little bit on this?

Matteo

Both Sitting Duet was made as a translation of a score, which for me seemed to follow on exactly from Hands, which is also written from a score. Only Both Sitting Duet was somebody else’s much more elaborate score – Morton Feldman’s in that case, as opposed to my plodding flat music.

Jonathan

You are never going to let up on that, are you?

Matteo

No.

Jonathan

Well, I am going to play Haydn all the time.

Matteo

But the other two duets were not researching scores; they were not made with the same idea of translating a score.

Jonathan

There was a certain point when I thought that a lot of the dance that I was seeing and experiencing, apart from ballet, had let go of pulse. I understood that this was perhaps to do with the dance needing to assert itself as an art form in its own right, because for many years it was seen as a sister art form to music.

What I also saw was that there was a particular time of dance pieces, which had become very familiar to me, and it has to do with weight-based contemporary dance, whether that be Limon technique or even contact improvisation, where the time of the body that you are dealing with is the time of the body falling. So there is quite a similar time across different pieces. The only person who was doing something different from that, was Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker.

Rhythm turns listeners into participants, makes listening active and motoric, and synchronizes the brains and minds of all who participate.

(Oliver Sacks, 2008, p.266)

Jonathan

The thing about trying to work with rhythm… When I was working with hymn tunes, there was a sentimentality around them and an irony that I could pull out of it, but there was also something about the full squareness of it that I could push against rhythmically in dance. But when I took away that kind of music and tried to work in silence, I found it very difficult to find my way through the rhythm: I had no scaffolding.

So the scores thing started with Matteo suggesting a way to notate rhythm on graph paper. The only other person that I know who did that was Shobana Jeyasingh. I had seen one of the scores, which Kevin Volans had shown me, which was for a piece he had written the music for. He was so astonished because before he had written a note, Shobana had already sent him the score of the dance.

And the other thing that comes out of it has been made clear to me this year: I taught a workshop in Berlin, and we were in a room in the former Berlin Bus Depot, which was in the process of closing. They had given a studio to the dance course, but the swing band of the Berlin bus drivers still met there to rehearse, playing Bert Kaempfert medleys, which I like, and they were in the next room with only a thin partition between, and it was impossible to hold a choreographic workshop because I just wanted to sing along. So I had to take the students into a dilapidated kitchen, and we had a whole day ahead of us in there, and I didn’t know what to do, so I got them to write scores for pieces that they could not practice because we did not have enough room.

I think they hated me by the end of the day; they must have thought the exercise was so academic and arbitrary. And yet even I was astonished when they worked out and performed the scores the next day, because the level of choreographic thinking was extraordinary. I was surprised, because in some way I had always associated choreographic thinking with a certain sensory experience within the body, but it was interesting to see that, of course, there is a sensory world that you work with physically, but there is also this other thing which is more abstract.

Matteo

Patterns?

Jonathan

To do with patterns, but what these students did, seemed more than pattern; it was a kind of abstraction that could also appear deeply personal. It reminded me why I like working with scores, and it has to do with quieting the sensory experience of the body, which can often draw you back into a place that is familiar. Body patterning is so powerful that it will draw you back to what you always do. The graphic experience – something to do with the act of writing or drawing – seems to release an imagination different to the imagination released by moving or researching movement.

Matteo

The composer Morton Feldman often talked about notating music in order to slow him down, because of course you go to a piano and your fingers will play the chord you are familiar with playing, and it is very hard to break those patterns. I have even tried things like playing the piano backwards. Feldman worked very much at the piano, but notating as he went along, in order to avoid those habits. So even for musicians I think the act of notating, and thinking about how to notate something clearly, gives you ideas of how to go on.

Jonathan

I think in dance we tend to think a lot about going into a room and researching movement, and Matteo taught me to risk that you don’t go in and research, you just go in and make something – and then leave.

Matteo

As soon as possible!

Jonathan

I have slowly built up a trust in the fact that you can make a good decision quickly, and the thing that takes you hours and hours to find is not necessarily richer. I was reading Allen Ginsberg’s essays recently and he talks about ‘First thought, best thought’, which came from his Buddhist training.

When we work we are quite old fashioned, in that we start at the beginning and go forwards, and we make one thing a day. A ‘thing’ is whatever we want a ‘thing’ to be. And then we try to have the discipline to stop. Sometimes we have stopped after one hour. Deep down we want to go on, because we think we ought to, but when we have the discipline to go home, we actually continue working unconsciously in a much better way; and we can’t wait to get back together again to continue the next morning. It stops being an exhaustive process.

I find that when I am making a piece, there are a number of levels of working. One is that there is the smell, or atmosphere, of the thing, and you don’t know what it is, but you sense it. Then there is some kind of visual image, which you should not trust, but nevertheless you store it away someplace. And finally, there are all sorts of activities which you do not know whether they are useful or not, but you do them anyway. Before we had made Speaking Dance, I spent three months reading only contemporary playwrights, but I did not know why I was doing it.

Guy

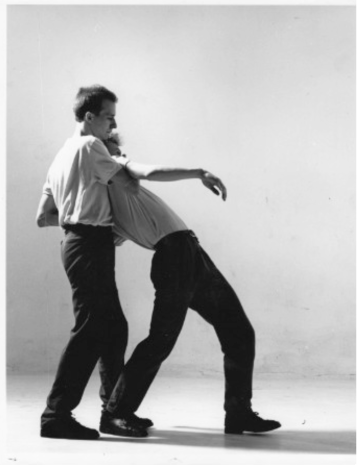

I would like to show the next video: a fragment of The Stop Quartet (the last part of the piece).

DVD of The Stop Quartet, final section

The dance is synchronous, not literally with regard to the movements, but in the way in which the dancers divide time, run through it and let it converge in stops. Even if real contact is rare, the dancers are intimate partners in rhythm.

(Myriam Van Imschoot on ‘The Stop Quartet’, 1996)

I have this memory of you telling me that you only set the footwork, and that the rest of the body movements were kept very free.

Jonathan

Yes, the upper body movements were often – William Forsythe has a nice name for it – ‘residual movement’; the accidental movement that happens by going from one place to the next place.

The footsteps came from a technique like ballroom dancing manuals, where you have boxes with numbers in and you put your foot here on number 1, and then on number 2 and so forth. Every section of the piece has a different pulse and even a tiny change of pulse completely alters the body. With The Stop Quartet it started out with Henry [Montes] doing something very slow, and it was very awkward, but then I asked him to do it 4 times faster, and he couldn’t help but make that flow of residual movement. He is a New Yorker of Colombian extraction, so there is a certain dancing body present there already that somehow resurfaced. As soon as I had seen what he was doing, I copied it.

It is an example of something that I think Matteo and I have worked with a lot, which is to set up a very formal structure against which you push. And from this, then many very informal possibilities and freedoms arise, sometimes to an extreme degree, but often unspoken. I found in performances of Speaking Dance, that there is very fast alternation between us, and we can actually change the speed of it, for instance radically slow it down and then speed it up again within seconds, without prior negotiation.

Guy

It seems to me that it has been a long journey, a long desire, to go into language like that?

Matteo

Musically I have always enjoyed setting text and been very frustrated with finding the right text. When I was much younger I became disillusioned with the fact that poetry is too heavy, it has too much there. But at the same time that Jonathan was secretly writing what turned out to be the first text for Speaking Dance, I was writing something for Siobhan Davies where I was also using language in a not too dissimilar way. I was looking for language that was very plain and did not have too much meaning in it, so I took Italian folk songs and translated them very badly into English, and somehow that gave me permission to do what I wanted to with it. And it was after I played them to Jonathan that his writing came out and we kind of – I don’t know – was that at the end of your writing? I can’t remember…

Jonathan

Yes, after he played me the music I said, ‘Why don’t you come round to my flat tomorrow, and I will show you what I have been doing, because it is the same.’

Matteo

It was the same, but we honestly had not discussed it at all – it just seemed the right time to introduce language in a different way into the work.

Jonathan

When we made Speaking Dance we thought we were making a piece about language, but we realised afterwards that we were trying to move towards making a music piece, which was what we wanted to make after we had made two movement pieces. And somehow the language is not the primary thing in Speaking Dance, but rather the thing that mediates between the movement and the music, with rhythm and counterpoint remaining the common denominator.

Matteo

It always seems to me that rhythm of speech produces rather boring music, whereas the musicality or the tone of speech might be more the clue. Like Debussy for instance, in the opera Pelleas and Melisande, it is the tone of the French language, the melody of it – that seems to be much more apparent.

Guy

If you go through the three duets and use similar research principles or the knowledge that you have about structure, do you find that Speaking Dance was different from the other ones, and if so, in what ways? In the musicality of it? Or the composition?

Jonathan

It is not so different in how we made it, it still has a lot of quite simple counterpoint, very fast alternation and things like that, and it is rhythmically not dissimilar to the other pieces. But the big leap, I think, was how the piece went from A to B, which was a more unexpected journey than with the first two duets.

Guy

Can you expand a little bit on that?

Matteo

We ran out of words and I panicked, I felt we should throw away the piece. But Jonathan persuaded me that we could actually do something else with it. He suggested that we could drop the fast patterning of words and sing instead, for instance, or get up from the chair and wave our arms about.

Jonathan

I said, ‘What are we good at?’, which is not very much, but we scraped together some things that we knew we could do. That was our principle for how to continue: ‘If we run out of words keep going by whatever means necessary’.

Matteo

Yes, so having got over that first obstacle of ‘You have broken the surface of this piece’ – it took me a long time to accept that – but once that was absorbed, it seemed like anything was possible. At lot of it was actually found material that we already had, which we reworked or kind of slotted into place quite quickly, you see – unlike The Quiet Dance, which was agonising, very slow, detailed work from beginning to end.

Jonathan

But there was a performance of Both Sitting Duet in Leuven, where somebody who had seen it before came backstage afterwards and said, ‘There is something wrong; the first time I saw it, I felt that each part seemed to freshen itself and draw my attention back in, and now it all seems to pass in a blur’. And we realised that we were not fulfilling an idea that we had had about performing it, which was that every part must have its own energy and start fresh, as though it was the beginning. And we weren’t doing that because it had gone well in performance, so we had been seduced by the rhythm of the whole piece.

But after that, with Speaking Dance, Jerome Bel came to see it and he said, ‘There is something wrong, it is not connecting for me, this sectional thing, I can’t make sense of it.’ And he was right, and it was exactly the same as Both Sitting Duet, but in reverse, in that we realised that as we had become more confident with performing Speaking Dance we were taking longer and longer pauses between sections. We felt that it was nice and relaxed, but in fact when we had first performed it, we had had a really sharp timing in the gaps, so that the sections ran invisibly one into the next.

Matteo

We were struggling with the continuity of it.

Jonathan

Yes, so then we went back to that sharper timing in the gaps, and the sense of the piece reappeared. But it was interesting to discover that what worked for a through-written piece, which was to be absolutely sectional, didn’t work for a piece that was already in sections. With a piece that already in sections you had to run one thing into the next in a very smooth and rhythmic way, otherwise you lost the continuity and the audience couldn’t make sense of it – they couldn’t connect the separate parts.

Guy

Shall we have a look at Speaking Dance?

Jonathan

This is a very rough video taken live in Poland.

Video clip of Speaking Dance, live recording

Matteo

It is so fast – I had forgotten how. When we do it now it doesn’t seem so fast anymore.

Guy

I think this is a good place to round it up here. We have covered a lot, and it has been an amazing journey – 15 years in this hour and a half. Thank you to Jonathan and Matteo for rounding off this series of talks in a very beautiful way.

Jonathan and Matteo

Thank you.

Books:

Sacks, Oliver; 2008, Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, Vintagebooks, New York

Burrows, Jonathan; 2010, A Choreographer’s Handbook, Routledge, London and New York

Eksteins, Modris; 1999, Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age, Mariner, Boston

Works mentioned in this talk:

Hyms, 1988

Hands, 1995

The Stop Quartet, 1996

Weak Dance Strong Questions, 2001

Both Sitting Duet, 2002

The Quiet Dance, 2005

Speaking Dance, 2006

Comments Off on the musical body