the mythic body

talk one

November 2008

Lilian Baylis Studio, Sadler’s Wells London

The Mythic Body

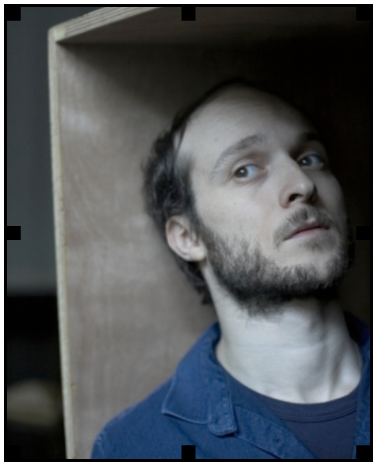

Guy Cools with Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui

As a child, the Belgo-Moroccan Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui (1976) wanted to draw reality. When the two dimensions of pen and paper were no longer enough, he began to dance. Dance as a temporary sketch of reality: the drawing disappears when the movement ends. From dancing he turned to choreography: his shows are story books in movement, which speak indirectly about the world around us, the near and distant worlds. And preferably about both worlds at the same time in a dance language which brings together the best of very diverse styles and traditions to create a surprising new entity.

“Our body is our destiny.”

(Keleman, 1999, p. 11)

Emma Gladstone (Producer, Sadler’s Wells):

All the artists who Guy has invited are people that he knows well, whose work he has programmed or helped to produce, or who he has worked with as a dramaturge. For me there is a benefit of catching a dialogue between two people who know each other rather than a formal interview. For that reason I’m delighted to welcome Guy with Larbi.

Guy Cools:

I want to thank Emma Gladstone at Sadler’s Wells, who, with the support of the Jerwood Studio at Sadler’s Wells , has organised this series of talks. For me it is also a result of looking back and trying to clarify my own ideas about dance in relationship with the artists I have worked with.

I am very happy that Larbi is the first one. I think we met at the very beginning – when he created his first dance piece, Rien de Rien, at the Arts Centre Vooruit while I was still the programmer there.

That is where our relationship started, and then, when I decided to quit the job of programmer to go back to the creative process, one of the very first productions that I was invited to support as a dramaturge was Zero Degrees, which was created here at Sadler’s Wells. I think all of us who were involved with Zero Degrees feel that it was a very special time.

For these talks I wanted to invite artists who I am close to and have a friendship with. But I also looked for an angle to frame the talk, and from which to talk about the work.

In Larbi’s case it is a little book which is called “Myth and the body”, which I discovered while we were collaborating together on Myth. The book was published in 1999 and it is a series of transcripts of lifelong talks that were held by Stanley Keleman, who is a specialist in somatic therapy, and Joseph Campbell, an eminent scholar in Western mythology. The talks were held from the late 70s to the late 80s, when Campbell died.

The main subject of these conversations was that mythology is about the body, and that all myths talk about the somatic evolution of the body – birth, growth, transformation, and death. It is a tiny book, but beautifully insightful.

Since Myth was the last production we worked on together, and since it was presented here at Sadler’s Wells, I would like to start with Myth. Can you remind me what the whole genesis of that production was? You changed the title a number of times, which I think was important…

“A mythic image is the shape of anatomy speaking about itself. The serpent of mythology is the spinal cord. […] The cortex is the thousand-petaled lotus, the crown of thorns. This makes mythic image incapable of being a reality apart from somatic reality. Mythic image is the body speaking to itself about itself. Myths are scripts of our genetic shape in social language. They are patterns of embodiment: they show us how to grow our inherited biological endowment into a personal form.”

(Keleman 1999, p.3)

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui:

Originally Myth was supposed to be called Trauma, which is a very ‘heavy’ word… at that time I was thinking about how to deal with problems, ‘childhood problems’…. I was 30 and I felt, ‘when am I ever going to get over these things?’ I like my work to help me overcome personal issues, and, as I had been working with the dancers for a long time (some of them for over 8 years), I felt we could go into a theme like that. But then I felt the word was very negative, and to give that to the audience felt not much of a gift. You already have enough problems of your own.

As we were going into traumas, especially in a ‘healing’ way, we discovered that it can be a dangerous word as well. You always think ‘healing’ is positive, but as we were researching around healing, we were finding that people wanted to heal people from things which were very normal, like being gay. So to go from ‘trauma’ to ‘healing’ didn’t feel right either.

Slowly we came in a very natural way to psychology, and then to mythology. What I like about mythology is that it doesn’t have a real morality. It is more like cause and effect: ‘if you do this, then this happens’. They are totally untrue stories – I mean, nobody believes them – but at the same time they create an image, and this image helps you to understand a psychological condition.

I like myths because they have been part of my life since early childhood. When I was studying Latin, the Greek and Roman myths were part of my education. At the same time I am a Muslim, so I have a lot of Islamic influences, and Catholic influences as well, because I grew up in Belgium. So all these things were already there. And we were delving and searching. Trying to make sense of them and trying to see how we can recognise ourselves in these stories. We started to talk about the colours in mythologies and all the gods. A bit like Hinduism, which feels incredible because you have all the archetypes – so maybe the word ‘archetype’ is also important, because it helps to define all the colours of the rainbow.

Suddenly it wasn’t black and white anymore, like in most religions – good or bad with nothing in between – but it felt like: ‘there’s red, there’s yellow, there’s blue…’. All these gods who have a different intensity. And all of them together created a sense of completeness.

As I was finding the cast I had 21 characters on stage, which I liked as a number because it was very symbolic. Like the Tarot cards – I don’t know if you know that there are 21 of them: The Arcane cards.

I like to play with numbers. At the same time we had scenes which were very concrete: For example Christine (one of the performers), who was a mother figure who rejects her just born child.

What do we do with a situation like this? How do we deal with that? How does a child deal with it? How does a mother deal with it? It became a very complex piece because you never felt you understood what was the right thing to do. You didn’t have the hero and the villain; it just constantly felt like, ‘well, the hero is not so nice, and the villain is actually not so bad’. It felt closer to reality.

Opposites are the tensions that are part of the formative process. When we can embody these tensions, we form our individuality. We are foolish and wise, wild and tame.”

(Keleman 1999, p.64)

Guy

A lot of your work researches these binary opposites: male/female, earth/heaven. There is a book called “The Eye of Shiva” by Amaury de Riencourt, which was recommended to me by Akram Khan (- he used it as a source for Kaash), and I think he got it from Anish Kapoor, so there is a whole journey of collaborations and influences.

The essence of the book, which I think links to your work, is that originally man was living in a magical relationship with nature and the environment. And then, when mankind started to develop a scientific (or rational) consciousness, East and West developed in different directions. Where the West would think of these binary terms in opposition, Eastern thought would approach them in a more complementary way, not choosing between the two of them.

What is it that attracts you to Eastern forms of art, which you have been exploring more and more recently?

Larbi

Well, there are many ways of explaining it. For instance, in the Japanese art form of Kabuki, a character can be many things at the same time. He has a solo that creates with a fan, and the fan can be the bow, later becomes the arrow, or at the same time it can be a knife that stabs you. Also the actor becomes many things. When you see Akram Khan’s traditional work, you see him becoming as much Krishna as Shiva; he is all of them, all the gods.

That’s what attracts me as an actor, as a dancer, as a human being: to allow yourself to be much more than just one thing. Not to be defined by what people see in you, or by what you see in yourself. No, you can suddenly be transformed. In a work like Zero Degrees, I definitely wanted not only to be the victim, but also be the other side, and understand that you are both, always.

Guy

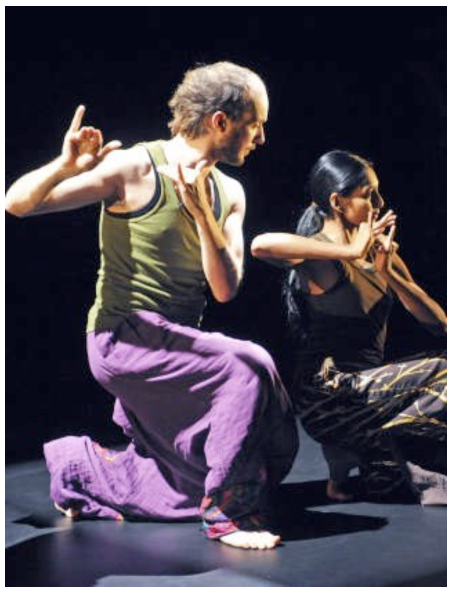

One of your most recent projects has been an exchange with Shantala Shivalingappa.

Larbi

Shantala is a classical Indian Kuchipudi dancer. I went to India to work a little bit with her and she introduced me to that particular style of dancing – which is something between bharata natyam and kathak (which is what Akram does). I have a million reasons why I wanted to work with her, but what was interesting for her, and made her want to work with me too, is that she had been doing a lot of singing and also a lot of dancing, but never the two together. This is something that I do a lot in Myth, and also in other pieces: I try to be the instrument as much as the one playing the instrument. She was interested in trying this. So suddenly we were trying to dance whilst singing the song, which was really very, very difficult. But those little moments when it worked, it was uplifting. It is harmonising.

Both of us got attracted to each other and also our voices matched – we felt very in tune. We started playing around the theme of ‘Adam and Eve’, man and woman together, something very innocent… like the beginning of a story. In my work with Akram there is something of a fight or union, but with Shantala there is no fight – just this sense of discovery.

Guy

I’m interested because you just mentioned it as her interest, but also as part of the essence of your work, that is the integration of the voice in the human body through singing. I remember that in Rien de Rien the discovery of that, through your collaboration with Damien Jalet, was something that you described as a somatic experience.

Larbi

Yes.

Guy

Since then you have not only developed it for yourself, but you also ask all of your dancers to integrate that.

Larbi

Maybe I should give you the history…

I started to work in 1999 with Damien Jalet, who is a dancer but also a singer. He works on Italian traditional songs, which means that they are often not written down. They are songs that would be sung in certain villages in Italy during Easter – mostly religious songs. Religious in the popular sense, so not necessarily in church, but by villagers who just sing harmonies that are very powerful. In voices which are very nasal. I didn’t know this kind of music at all; I didn’t grow up with it and when Damien brought in this element in the creation of Rien de Rien – I got goose bumps. I was totally struck by the harmonies, it was like it was the first time that I understood harmony in music and what it meant. How one voice and another voice create something almost like a third voice. When I got that feeling, I never wanted to lose it ever again.

And so I started learning how to sing. He taught me how to go into the harmony, which is a very physical thing to do. First of all it was just based on memory – I have this fear of reading notes. It always feels like I can’t do it; I don’t have the training.

He started to teach me and would be using his own voice. Slowly we were harmonising, and then we were combining this with movements – he was dancing in front of me and I was behind him – a very simple image that is often used in choreography, four arms create a sense of a Shiva figure. This was in 2000. It felt necessary to do the movement whilst singing and necessary to sing while doing the movement.

That was my first experience of the voice. Then I was very lucky to meet very, very gifted people in music. I went from Italy to being interested in Corsican music, and then from Corsican back to Spanish music – whenever I feel or hear something that really matters to me or resonates with me, I will go and try to understand it. Shantala was using a lot of Ragas, using the voice in a very different way than I was used to. It felt very attractive, but not in an exotic way.

Guy

Going back to Myth and its creation process: What I observed and what was so beautiful to see, is the way you work like a contemporary scientist… like a science lab, where all the dancers have a lot of autonomy. You give them subjects and ideas, but you also give them a lot of…

Larbi

Responsibility.

Guy

… and freedom to research these ideas on their own. The first week of rehearsals – I remember when we were in the studios of PARTS, we had 2 studios and maybe 10 different groups of 2 or 3 people. It seemed that the way to keep these people together as a group were the yoga class in the morning and the singing class with Patricia Bovi in the evening.

Larbi

Dance classes never really spoke to me. I mean, I love dance, but the class was never something that I felt brought people together. Also, working with people who have such different styles, finding a movement style that would fit everybody is impossible.

So it became obvious that we needed something else. I was really getting into yoga and understanding more about it – about the inside leg, about the spine, about how to be at one with gravity. Because really, standing up – what is it? I was trying to find a real physical straightness, which is not the straightness you get from the teacher in school (when they say, ‘sit straight’), or in ballet, when they say ‘stand straight’. The real straightness is something that is really effortless. It is like a feeling where suddenly your shoulders are not hunched up but opened up. You don’t feel the weight of the world on your shoulders – you actually feel that it all glides off you – and you feel the only responsibility you have is to be.

I started to teach the dancers the little yoga I knew. It was about a kind of awareness and also just being very practical about how to get the body to be more flexible – which also makes the mind more flexible. It is the same thing – the body, the mind – I hate this kind of separation. When I feel anger, my liver is angry. When I have an emotional problem, it is the stomach. When you want too many things, you have a problem around the neck; like when you have an existential crisis. And if somebody dies in your family, and you are afraid to die or afraid to be left behind, it is most of the times the lower back that is the problem.

What was interesting is that as I was taking things from different cultures, it was always the same things that were coming back. When I was in China I was doing a lot of acupuncture because it was a very stressful period there, and they were telling me the same things that I already heard when I was learning yoga, when I was learning kung fu, and in tai chi and in singing as well.

Singing and yoga were the two things that very logically brought the group together, when everything else separated it. Then, when we were putting together things slowly, they started understanding co-existence.

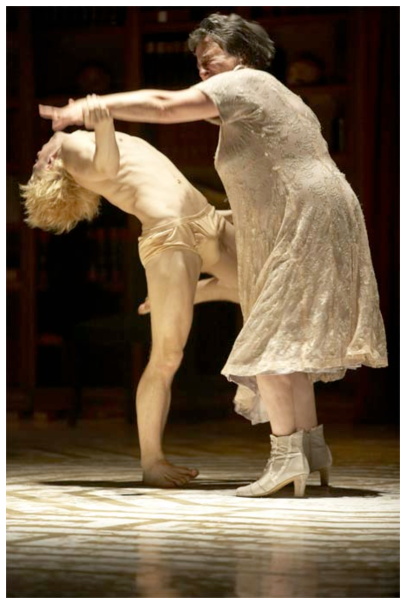

Video clip of Myth (the last 10 minutes of the piece)

Guy

I have chosen this fragment because I want to show another fragment of Apocrifu later, and somehow Apocrifu starts where this piece ends.

I am reminded that two of its main criticisms – and ones that made you angry – were the complexity and the overt religious symbolism, especially in this final section. But to me they are both very essential to the piece.

The complexity is something I remember us fighting about, and you being very stubborn, saying ‘I’ll keep everything in, and the challenge will be to compose it in such a way that all these images belong together.’

Why was it so important for you?

Larbi

As we were making material a lot of things got created and all of them made sense to the people involved. Then what most directors do is ‘kill your darlings’; you have to cut, cut, cut, cut… I’ve been cutting all my life, and I like cleaning up, making it very pretty – and I thought, ‘what if I don’t; what if I keep everything, what if everything gets a place, what if I don’t reject anything?’

I was at the time thinking about how to handle rejection; how to handle ‘this is not going to have a space’, and ‘no, your solo is nice, but this one is better’. There is always a hierarchy. With this piece, I didn’t want this. I wanted everything to get a space. Because that is what it was about: finding a space for everything, like in an encyclopaedia.

My image was a little bit like homeopathic science, where the active ingredient is always diluted in other stuff. It’s not just pure vitamins, which are sometimes bad for the stomach because they are too harsh, too radical, too clean. Sometimes you need it coming from an apple. The body is very smart; it can take things. And I believe the audience is also very smart and can take out what it needs for itself.

The piece became more like a canvas. As a painting it was acceptable. I remember a journalist from Greece who had seen it once and told me: “I think it is too much.” He was in Antwerp, so I brought him to the cathedral there, to see the sculpture at the entrance, which is really huge and full of apostles and all of that. You can’t take it in, it is just too much. And I asked him, “Do you think the artist is doing too much here?”

He understood. When you really focus on the cathedral, you can see the story.

Also I do like this kind of work when I am in the audience myself… Maybe it is my generation. We grew up with MTV – you know, watching MTV, being on the computer, doing your homework and listening to your mum at the same time – so I feel like it is also part of who I am. I like being very alert and awake, and able to take in a lot of stimuli at the same time. For Myth it was a choice more than a flaw.

One of the intentions of a mythological system is to present evocative images, images that touch and resonate in very deep centres of our impulse system, and then move us from these very deep centres into action.

(Keleman 1999, p.34)

Guy

We were trying to bring alive unconscious issues starting from the personal experience of the performers, and then we wanted the audience to be able to recognise themselves in it. This quote in the book made me understand that what we were possibly doing was creating myths. As I told you, I think, I discovered the book towards the end of the process.

And then I got at least one personal, very subjective confirmation that we were able to do that. I think that it was not by accident that it was in Greece…

After the performance there in Kalamata, I had to give an audience talk and I discussed some of the issues that we are dealing with today. After the talk a woman came to me who had seen the piece before, and she told me this personal and very touching story. She said that all of her life, in her dreams, she had an image coming to her, and then she had seen this image literally being recreated in the performance – in the midst of all these other images. Whilst she hadn’t dreamt about it for rather a long time, it had come back to her the same night in a dream, but she felt that it had changed its quality. She was kind of unclear about what it meant for her as the experience was so recent, but it had deeply touched her. It was a very, very touching moment for me to understand, too.

Larbi

It was a very interesting journey for us. In places like Greece they know about mythology. They recognised everything. Like the moment when three wolves come together and then suddenly they move together – they knew it was Cerberus, the dog with the 3 heads that guards the door to hell. We constantly felt they knew each image, grasping and appreciating every single symbol.

In Spain, it was more the Christian part which was appreciated. And the place which was the hardest was actually France, which also makes a lot of sense because in France they hate religion, and it felt like they did not want to talk about faith – they felt like, “Are you here to convert me or something?”

The element of humour that is in the piece is, I think, a very Anglo-Saxon humour. So for instance in England I could feel that those elements were picked up, but in France, because people don’t speak English… the balance was wrong.

With all the touring that I am doing now, I have realised how culture specific countries can be, and how they, without knowing it, are very connected to their roots.

Guy

I would like to introduce the next video fragment. In the end of Myth we have this librarian figure who is almost collapsing under the weight of the books, and in your next piece, Apocrifu, there was a lot of research about…

Larbi

… the book – the power of books…

Guy

… and the written word.

Larbi

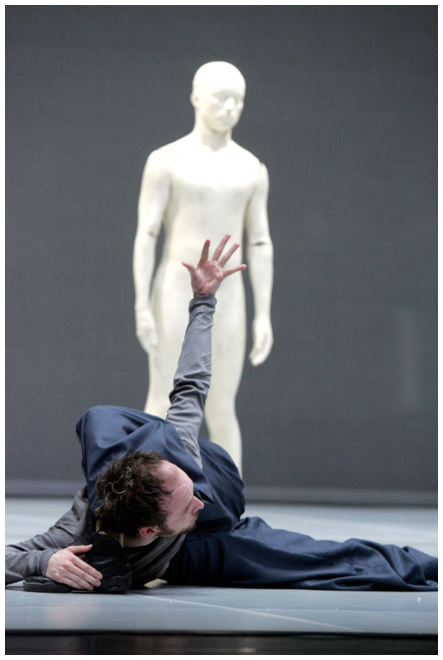

It was also about rejection.

There are just 3 dancers, and I am one of them. I worked around the Bible, the Koran, and the Torah. We were juggling around as three dancers with these three books, and one of the things we discovered as we were doing research, was that some of the stories that are in the Koran are actually apocryphal.

I don’t know if you know what the word apocryphal means. They are words, or writings, that have not been accepted by, have not been introduced into, the Bible. So when the Bible was put together certain texts were not selected. The selected ones are the canon and the non-selected ones are apocryphal texts. Because of this word, I felt like something had been rejected… I felt rejected.

I have always felt it in parts of my life: only half Moroccan, only half Belgian, I am gay… there are a lot of things that pushed me out of the system, like these apocrypha. Then I discovered that some of the apocrypha ended up in the Koran. The Koran which is supposed to be the Angel Gabriel who came from God and whispered these words into Mohammed’s ear!

500 years earlier the same texts were already in some apocrypha. I was totally amazed to find that there is a source of the source, and that by having been rejected out of the Bible, it became another religion – it became Islamic. It became part of something else.

What was also fascinating was the story. It was one of the stories around Abel and Cain. The story was that Abel kills his brother and he sees a bird. A crow going into the ground, so he thinks, ‘oh, I should bury my brother like I saw the crow doing’. It is a nice story that is not in the Bible, but it is in the Koran, and also, I think, it is Torah 5 and 31 / 32. In 32 there is a comment on this, and it says, ‘he who takes the blood of one, it is as if he takes the blood of all, and he who saves the blood of one, saves the blood of all.’ It is about Abel. He wasn’t supposed to kill Cain, so it tells people when they read it, ‘you should know you should not’. This extra comment became in the Koran Sura 5. It used to be a comment, and then it became a real Sura, real teaching. I found that fascinating, to see where things come from, and how morality is being taken out of belief systems.

Guy

Larbi actually also tells this story in the performance.

Video clip: Apocrifu

Whether we like it or not, we are incarnated. We are bodies on this planet, and all myth and all stories seek the origin and the end of our somatic structure. Myth as story is the life of our body in one or another of its forms. We are all making up stories, finding stories, finding facts to talk about our somatic origin, its growth and its end. […] In telling your story, look for the somatic shapes.

(Keleman 1999, p.68-69)

Guy

Death is a very important theme in all your productions, from the very first one to the present. Can you talk a little about that?

Larbi

For instance for the solo, I was interested in old age or how to get heavier and heavier so the body gets harder and harder to control – there are very simple manipulations with which you can guide yourself very easily, so suddenly it becomes much more heavy, and you need more and more energy to be able to move the smallest thing.

I was inspired by an old lady who just needed to cross the street, and the time it took her was like an eternity. I felt like it was a totally different life, a different way of dealing with distance, with getting there, and also the appreciation of life, or the appreciation of a goal.

When I work with differently-abled actors, they have another speed, another way, another perception, but you can get to the same place…

It teaches you patience – and you then think how to apply this patience to yourself in order to get somewhere. For instance let’s say kung fu. I wanted to learn kung fu, but when I started to learn, I thought, ‘I will never attain it’. Then I thought, if that old lady can get across the street, I can at least get to something that is close to kung fu.

But to come back to the subject of death – it was something that was always present in my family. My dad died when I was 19, and this was a big, big shock. I did not have a good relationship with dad at all. He was someone I did not like, I did not want to become like him at all. He was the total opposite of everything I wanted to become. And as I grew older I was more and more becoming like him, so I was like, ‘how can I not become like him?’, when, actually, I am a reincarnation of my mum and my dad. I am them, they made me, even if I am an individual. And I can go to my left hemisphere and think, ‘I am an individual’, but I also had to accept that shadow side, that father side.

It did not have anything to do with the culture, because the Arab culture was something that I accepted totally. I was proud of being an Arab, but I was not proud of being the son of my father. He was not really proud of me, too – there was this tension…. But when he died, it changed everything. I could never prove him wrong.

He was someone who always told me: “You will never make money while dancing”. I can tell you, I make money while dancing. It is possible as an artist to make a living. But I think still today I am not beyond that fact of proving him wrong.

And then, 2 years later, my grandmother died. It felt like death has always been a very, very natural thing for me. But not for my mum. I could feel that she was always really affected by it… when it happened, she got a hernia, her lower back – she could hardly move anymore.

When you lose someone it is very important in the family to restructure, to find out ‘who does what? Because if you don’t restructure, you lose a function – you lose the father element, which can be an energy. It can be done by anybody. It does not have to be your father. It just has to be done. Our own education is about losing everything… and people always complain how they lose things. But they do not understand that it is not losing – it is transformation. You are changing, and gaining other things.

When you have a scar, it is new material. People always want them to heal, to become what they were. But I think, ‘no, you have to go to what you have become’. This scar tissue – it is really new tissue. When you go to primitive cultures where youngsters scar themselves, or when you get tattoos – what are they doing? They are being reborn, by changing themselves. On their 18th birthday they are like the Phoenix who comes out of the ashes. They want to have new skin. And they do it consciously. We have lost this, but at the same time we have not lost the urge to do it. I had a tattoo on my back when I was 23. Why did I need this?

I do not regret it because I feel that that was what I needed – this kind of ritual, this sensation of transformation, and it needed to be a very physical choice, something that I could choose, something that I could determine, that was part of my physical journey.

I think I will be a happy dead man. Because I think it is such a big transformation, and my whole life has been about wanting to change, to transform myself into something else. I think death is that ultimate transformation.

Guy

Having been a privileged witness of your work, there is a huge transformation of how you deal with these things. If you look at Rien de Rien, there is an anger which is very much projected towards yourself, and in Zero Degrees there is still this kind of fighting with yourself. But it is much lighter – fighting with the dummies… and then it becomes a lamentation, so there is a sadness.

And in the last piece, Apocrifu, it is about pulling yourself together. The message for me is that we are masters of ourselves, and that we do not need external things. It is very much about this maturity that you have personally gained, and also as an artist.

Larbi

It comes in waves… I think there are days when I feel totally in sync with the belief system I chose for myself, and then days when it makes no sense to me.

Guy

Shall we finish?

Add in bit more of an ending?? EG

To be embodied is to participate in a migration from one body form to another. Each of us is a nomad, a wave that has duration for a time and then takes on a new somatic shape. This perpetual transformation is the subject of all myth.

(Keleman 1999, p.76)

Books:

Keleman, Stanley; 1999, Myth & the Body – a colloquy with Joseph Campbell, Center Press, Berkely, CA

de Riencourt, Amaury; 1980, The Eye of Shiva – Eastern Mysticism and Science, Morrow, New York

Works mentioned in this talk:

Rien de Rien, 2000

Zero Degrees, 2005

Myth, 2007

Apocrifu, 2007

Play, 2009

Comments Off on the mythic body